The value of our trash should not be beautiful

Who pays for what you throw away?

Designers make the most beautiful trash

There’s a saying “designers make the most beautiful trash” as almost anything and everything designers make will someday end up being disposed of. At times designers also try to beautify trash. This keeps us in our cycles of consumption and consumerism, masking deeper problems with purchasing and purging, trying to feel good about it all. But our trash is not beautiful. It’s problematic.

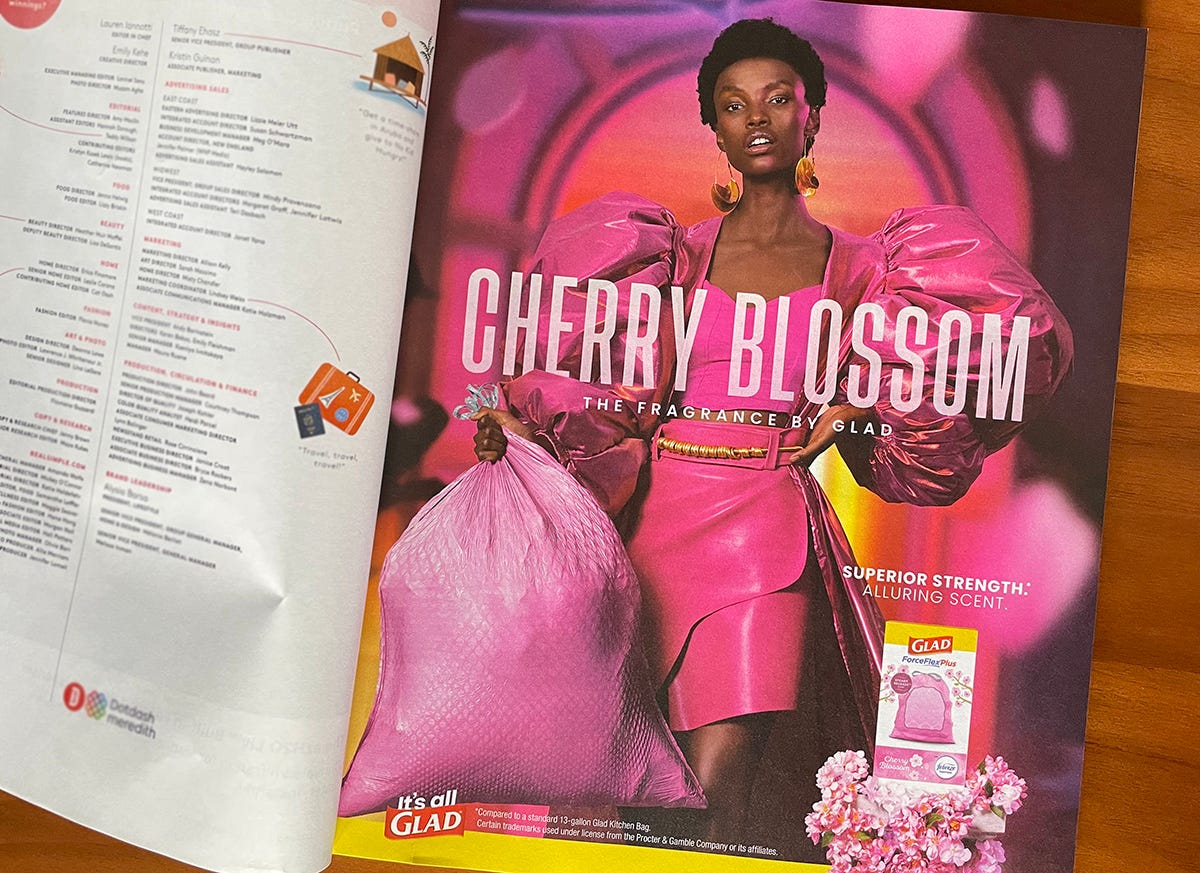

Recently I was flipping through a magazine when I came across an ad that jolted me - pink, scented, sexy trash bags. I’d never seen throwing away trash become so glamorized, and so problematic.

When we throw things away, they don’t really go “away”. There is no “away”. They go to a landfill where they sit for eternity. It might be out of your house, out of your bin, but it most definitely is not away. And on a planet with finite real estate, we don’t have finite places for our trash. Not to mention the fact that these bags are made from plastic - which is made from oil, a non-renewable resource. Even more dangerous than the materials used to create these bags is the mindset it implies - that we can, and should create more trash, fun trash, sexy trash, and that throwing the trash out is a glamorous act in itself. A quick google search shows me more ads of women in pink high heels celebrating the disposal of their color-coordinated trash. But we should not be celebrating the creation of trash or making more of it. This is exactly the opposite of the products, habits, and mindsets needed for a regenerative planet.

Cash for trash

In the same week that I first saw this ad, I took a trip to the recycling center in West Oakland near my home. As advocates for waste reduction and keeping as much out of landfills as possible my family sometimes goes out of our way to make sure things end up in what we hope is the right spot. We had accumulated enough styrofoam from various places to make a trip to the drop-off worth it. Styrofoam is extremely hard to recycle and often not cost-effective, as such there aren’t many places that will take it for recycling. It most often ends up in landfills crumbling, flaking, and polluting our ecosystems along the way. Styrofoam containers have been banned in most of California for some time, but they still end up in packaging. The massive recycling center I go to is in an area of industry and housing projects - a reminder of the impacts of environmental racism. It’s also surrounded by both homelessness and gentrification - reminders of the growing divides in our country. Every other person who is visiting the recycling center is in line to trade in bottles and cans for cash. I stick out for several reasons, one of which is that I’m not wanting or receiving any money for my trash, but just hope it won’t end up in the landfill.

In this mini village of compacted materials, sorted by type, material, and color, I paused, I can’t help but be mesmerized. It’s even kind of, dare I say, beautiful.

As I drive away I think about the bags, buckets, minivans, and pickup trucks full of recyclables that these people have collected to get money for. For this population - this trash, the bottles and cans others have tossed out is valuable. They can get cash for it. I would venture to bet that anyone paying the extra money for a pretty pink cherry blossom scented trash bag does not need to exchange bottles and cans for cash. Highlighting again, the inequities, the disparities in our culture.

What is the value of our trash?

In the Bay Area, we pay for our residential trash pick based on the size of our weekly pick-up. By default, everyone gets the same large recycling and compost bins for curbside pick up, and then the size of your trash varies - the smaller the can, the less you pay. The goal is to incentivize composting and recycling and throwing away less. On average, most residents have a smaller trash can than they do recycling and compost - visual cues for behavior.

Not everything can be recycled in curbside pick up - hence my special trip to take the styrofoam to the recycling center. I’d venture to guess most people don’t make this effort, but instead, just throw what can not be recycled into the trash. One new company trying to disrupt this is Ridwell - a new start-up making “it easy to sustainably reuse and recycle your stuff”. They will pick up hard-to-recycle items - clothes, shoes, plastic film, corks, electronics, and more. The catch, you pay to recycle. While we do also pay our regular monthly trash bills, that has been set up as a municipal service, something built into our lifestyles or calculated into rent prices. Ridwell, has good intentions and makes hard to recycle recycling significantly easy, but I can't help but wonder how many people are willing to pay even more to get rid of things? In affluent parts of the Bay Area and other “eco” cities such as Seattle, Portland, Austin, Boulder and others, there are a growing number of consumers willing to pay more for their trash to be specialty recycled, but on a mass scale - this behavioral shift is not yet here, nor the socio-economic means to pay for it.

Inverting Responsibility

In all of these instances, the burden of disposal is placed on the consumer. The circular economy strives to put the task of disposal back on the producer. If you make it, you must be responsible for taking it back and properly disposing of it or turning it into something else. Essentially, it’s putting an end to planned obsolescence by forcing the producer to want their product to last and to know what to do with it next instead of getting you to buy again - buying more and buying often. Can you imagine - if Apple had to take back every iPhone and turn it into a new iPhone? Or all of the cheap electronics on sale for the holidays - the gadgets and gizmos that are designed for gifting and usually don’t last past New Year's Day? If those had to each be returned to their manufacturer and not chucked out in the trash?

When I see this ad for pink trash bags - an ad designed to make me want to buy these the next time I’m at the store - or maybe even tell my “smart home device” to auto-ship it to my house - it makes me want to do the opposite - to buy less.

So there’s the trash we celebrate throwing away in sexy pink bags, the trash we mindlessly throw away with our trash bills on autopay not thinking about the expense, the trash we collect and exchange for cash, and the trash we will pay extra to have someone take. In all of these, we need to ask who is paying? who is profiting? We are all paying of course, in one way or another. We are on a shared planet.

As much as we can and should pressure producers to make more responsible choices in the end life of their products, we also have a choice to buy less and use less. As designers, we have choices in designing systems. These could be product systems, trash systems, use and reuse systems. How do we stop designing beautiful trash? And ugly trash? And instead, how can we design renewable and regenerative cultures?

Yes, and . . . there's all the brown trash, i.e. the boxes from Amazon and everyone that pile up so much in middle-class houses. Yes, it's recyclable in most places, and yes, the carbon may be less from one delivery round than everyone driving themselves to the store, but it sure makes big piles of discarded material very fast.