All the birds told me: sustainable fashion isn’t sustainable

Eco-trends also sell ideas, behaviors, and mindsets that are often not sustainable and go against their very efforts.

Shoes from recycled bottles. Jumpsuits from recycled threads. Tote bags from old sails. Jackets from recovered ocean plastic. Wallets from tires. Sweaters from goat hair. Sneakers from natural wool. All these products and more are being sold to us as “sustainable fashion”. Purchasing these things is meant to be good for the planet and therefore guilt-free shopping! However, these trends also sell ideas, behaviors, and mindsets that are not at all sustainable and go against their very efforts.

The eco-sneaker Allbirds made news in recent weeks as having fallen short on their earnings. The very headlines alone reveal the irony of sustainable capitalism - the brand didn’t sell enough, thus we need to buy more to keep it sustainable. Allbirds, which promotes itself as selling “sustainable shoes that will save the planet” and “reverse climate change”, had fallen short of sales goals, causing the stock to plummet, and headlines about tech bros favorite sneakers being in trouble spread across the internet. It begs the simple question - what was the goal? Was the goal to be a B corps, to give away shoes to those in need, to make shoes of natural wool instead of synthetic materials to reverse climate change? Or was the goal to sell, sell, sell - buy buy, buy - make, make, make?… The need to continually grow, sell more, and make more, is at odds with the very word sustainable which means to maintain.

Even if less bad, we’re still buying more

Allbirds is not unique in this, many brands are doing the same thing. Allbirds came along in s slew of brands and products not outwardly trying to sell sustainability, but trying to sell sleek, good design, oh, and by the way, sustainability is part of that. Rothy’s, Impossible Burgers, Imperfect Foods, and others all launched primarily out of Silicon Valley, around the same time.

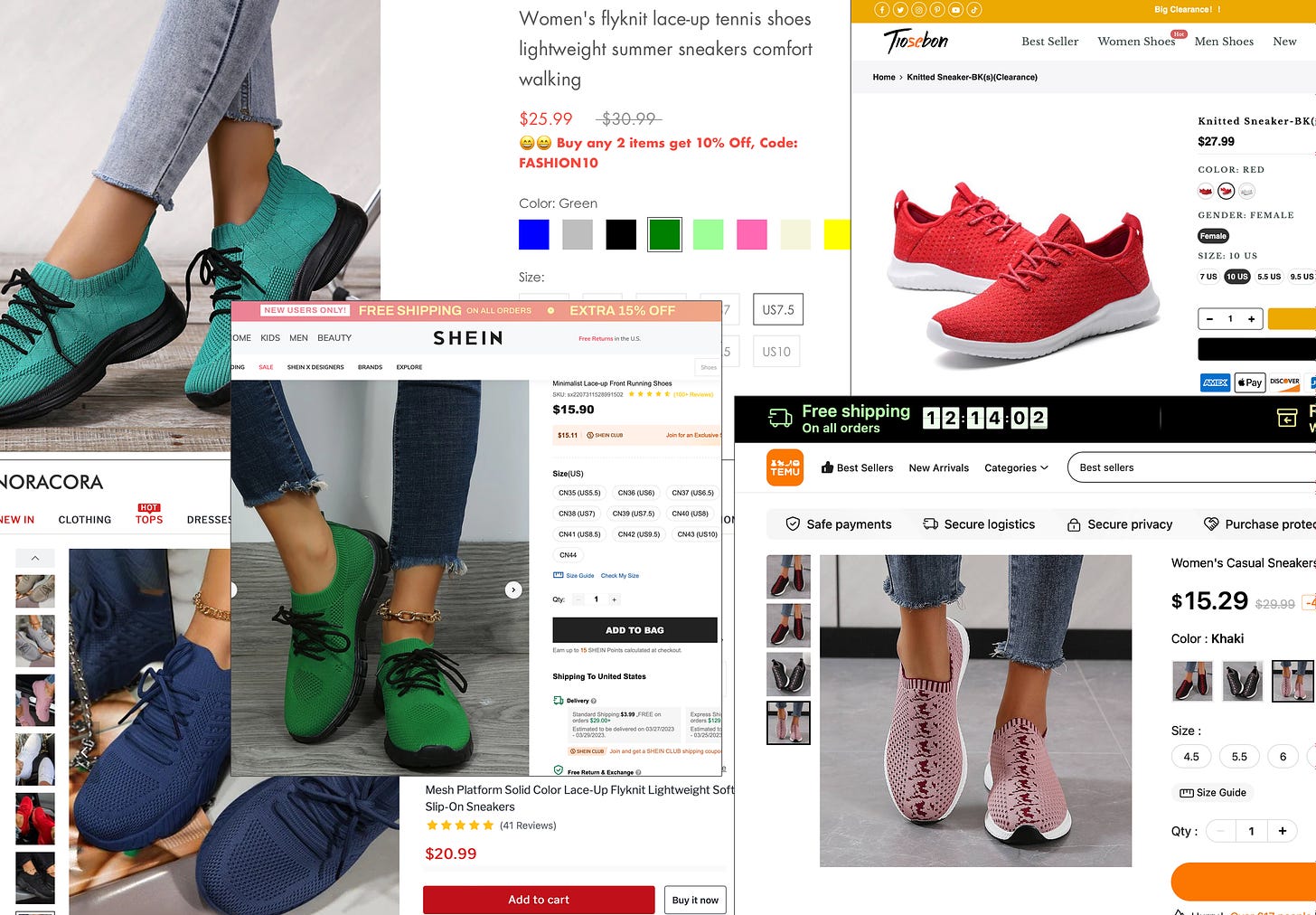

Marketing these trends encourages buyers, and also encourages knock-offs. The knock-off versions of course are not rooted in environmental impact, but in the look of them. Back in 2019, Allbirds itself made headlines for publicly calling out Amazon for doing exactly that - copying their look but not their sustainability efforts. Allbirds CEO Joey Zwillinger went on a publicity tour encouraging Amazon to steal their sustainability practices, not just their design, and tried to shed light on the impacts of the global fashion industry to consumers. But the problem remains - whether promoting the eco-shoe or the knock-off-shoe - the messages consumers receive in branding, advertising, and mass media is buy more, consume more, get more, get them in every color, get 2 pairs in every color for every mood for every occasion!

Greenwashing by Affordability & Class

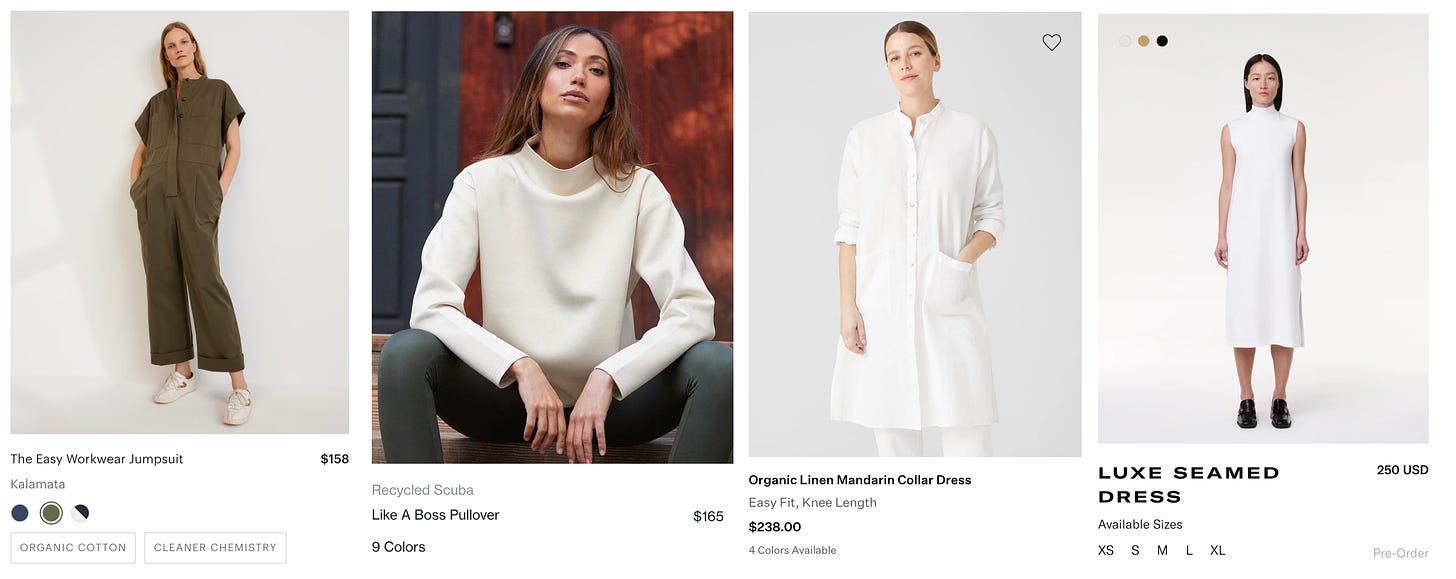

To counter this, there are in fact brands like Eileen Fisher, Everlane, Another Tomorrow, ADAY, and others that emphasize minimalist fashions - buying less, but paying more. The higher price point of these brands correlates with environmental and ethical standards in their production (or so they lead us to believe). At the same time, because of the price, these brands inadvertently market sustainability as for the elite, only for those who can afford it. It becomes a sort of greenwashing by class.

The economic crises, the slow erasure of the middle class, and the growing economic disparity will only drive this point further. When families are struggling to make rent, afford food amidst skyrocketing costs, pay for medical care, and other basic needs are then presented with a $125 eco-shoe, or one that looks just like it for $14.99, the choice becomes clear. While it may seem as though these cheap goods are helping those in lesser income brackets, the continual production and consumption of cheap goods just perpetuate the problem. The recent feature in the New York Times by Matthew Desmond, Why poverty persists in America, outlines the role of cheap goods as part of the larger systemic issues keeping the poor, poor. In order to produce goods that sell for such low prices, they of course need to be made with cheap labor, exploitative labor practices, polluting marginalized communities with their factories, and other destructive practices done in the name of making a cheap buck. Desmond's piece outlines the: “deeper structural forces at play, ones that have to do with the way the American poor are routinely taken advantage of. The primary reason for our stalled progress on poverty reduction has to do with the fact that we have not confronted the unrelenting exploitation of the poor in the labor, housing, and financial markets.” The issue of climate change, like poverty, like all wicked problems is complex, and part of a need for larger systems change.

Asking the bigger systems question

If we really wanted to save the world through buying eco-sneakers, we need to ask the deeper questions of who can afford them? who can not? where are they sold? where are they not? how do you get a job to be able to afford them? who gets those jobs? who has the education to get those jobs? who has access to that education? who decides wages? what is minimum wage? how many shoes does one need? why do we need so many shoes?... Asking these deeper questions, we can see that the answers are much more complicated than swapping synthetic materials for wool, and have more to do with socioeconomic class, education, well-being, mindsets, and larger systems.

The one brand that has done the most to create systems change in the name of clothing is Patagonia. While their higher price points (because of high labor and material standards) do keep them out of reach for many, they unapologetically encourages customers not to buy their products, to buy less of their products, to repair their products, to resell them, and do everything possible to keep them out of landfills. Most recently Patagonia founder, Yvon Chouinard gave the company away in the name of climate change - a stark contrast to those trying to sell shares and drive profits. It’s also worth noting, that Patagonia’s target audience is likely enjoying their gear while outdoors, in nature, a place they are trying to protect.

Meanwhile, amidst Allbirds stock fumbles, the company has announced a new strategy to “reignite growth, improve capital efficiency and drive profitability in the coming years.” Whether consumers are buying clothes and shoes because of the design, the trend, or the environmental impact, it remains rooted in capitalism and the need to buy more more more! Continual growth and profitability for the few at the cost of the many is not sustainable. For sustainable fashion to be sustainable - the thing we need to “sell” is shifting mindsets to regenerative practices. What might a fashion brand look like if it were designed by the factory workers making the clothes? If those people were empowered with wages and working conditions to be able to afford the very clothes they make for others. What if those who live in the communities where the factories pollute instead lived in ecosystems that cleaned the air and provided clean drinking water? What if we lived in a society that valued the environment, community, and nature as much as we value a cheap pair of sneakers?

P.S. For the record, I’m part of this all too as I own a pair of Rothy’s shoes. We all still need clothes to wear, but we can be mindful of how much we need, when and how we need it.

About high-end eco-products — sometimes in this economy an improvement starts at the high end, and gradually works its way down, by a combination of factors, including providers having saturated the early-adopter market. But as the Desmond article you so usefully refer us to says, providers of basic services to poor people, services like housing or banking, may be doing fine with their exploitative mode, and may have no desire at all to broaden or revise what they offer. And their poor customers having nothing left over for changing their consumption patterns, so the downward spread of the originally high end stuff won’t feel any call. Desmond is devastating on this point.

Interesting points here, particularly drawn to this comment on cheap goods perpetuating poverty.

"While it may seem as though these cheap goods are helping those in lesser income brackets, the continual production and consumption of cheap goods just perpetuate the problem. The recent feature in the New York Times by Matthew Desmond, Why poverty persists in America, outlines the role of cheap goods as part of the larger systemic issues keeping the poor, poor."