Dangerous unselfishness, bending the arc

Two reflections on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s impact on environmental justice - one historical, one personal.

MLK and the Environmental Justice movement

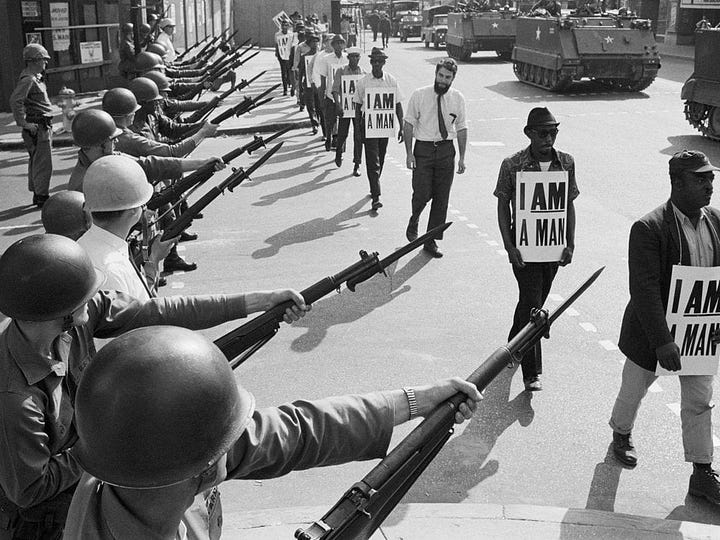

The day before Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, on April 3, 1968, he was in Memphis Tennessee advocating for the rights of Black sanitation workers who were on strike. While the black workers were paid far less than white coworkers, the fight was about more than just wages - their jobs were also more dangerous and dirty, routinely being exposed to greater health and safety risks. The strike continued after his assassination until workers were granted a better wage. Many in the Environmental Justice (EJ) movement point to this moment as the birth of the movement. This was a clear example of black workers being exposed to far more harmful environmental impacts in their jobs. The successful adoption of the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970, the Clean Water Act of 1972, the Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 and others have all been attributed to Dr. King's tireless advocacy for social justice. Dr. King knew that issues of racial justice were interconnected with poverty, the environment, healthcare, education, and gender justice. The evidence of environmental racism is still seen today as around the world pollution, contaminated water, and toxic products disproportionately affect the lives of people of color.

In his speech, “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop”, that Dr. King delivered to the supporters of the sanitation strike, he proclaimed “let us develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness.” At that moment he was calling on everyone to stand in support of the sanitation workers and to do everything they could to help the cause. In recounting a story of a Good Samaritan Dr. King recites:

The first question that the Levite asked was, "If I stop to help this man, what will happen to me?" But then the Good Samaritan came by. And he reversed the question: "If I do not stop to help this man, what will happen to him?"

That's the question before you tonight. Not, "If I stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to all of the hours that I usually spend in my office every day and every week as a pastor?" The question is not, "If I stop to help this man in need, what will happen to me?" "If I do not stop to help the sanitation workers, what will happen to them?" That's the question.

If we embrace a kind of dangerous unselfishness toward environmental sustainability - how might we live? What might we design? To consider the impact of our own trash, our own actions, and our lives in relation to all those affected by its supply and disposal chain. Instead of mindlessly ordering an endless stream of Amazon deliveries, prepacked meal kits, super-sized lattes, fast fashions, and disposable goods, what if we rethought these actions not because of what they provide to us, but what they do to the greater good?

Most designers live and work in privileged positions untethered from the consequences of design. We don’t collect the trash thrown out by design studios, factories, or our homes. We don’t work in or live near the factories that produce goods polluting the air quality.

What might it mean to design dangerously unselfishly? So that our impact, from production to consumption, did not destruct but rather renourish the people and environment surrounding us?

What new products, services, and actions might we create? And in doing so, how are these actions of dangerous unselfishness connected? That the climate solutions we need to design do not just solve one problem but solve many. The Memphis Sanitation strike wasn’t just about wages, but also about health and safety, long-term health impacts from toxic exposures, access to food by getting off food stamps, ensuring education for workers' kids, and improving the overall quality of life for individuals, families, and communities. The same is true for regenerative designers today.

Putting my hands on the arc bending toward justice

In 2009 I was asked to contribute to an exhibition “I Have a Dream” by the Gabarron Foundation in honor of what would have been Dr. King’s 80th birthday. In many ways, I still find it strange that I ended up in this exhibition. At the time none of my work was about race, social justice, or anything I could think of as being directly related to Dr. King. But if everything is indeed connected, I can draw the circle that led me there.

In 2007-2008 I spent a year traveling between different artist residencies, exhibitions, and conferences around the world. I had put everything I owned into a small storage unit and lived in China and the UK, while also spending time in South Africa, Spain, Germany, and other parts of Europe and the US. This was an interesting time to be an American abroad as the 2008 presidential primary was underway with elections full of hope and change. That fall I was invited to participate in a city-wide public art exhibition in Madrid. A reporter from El País (the Spanish New York Times) came to interview me. While she asked me about my work in the exhibition, what she really wanted to talk about was the election, and did I think Obama could win. The photo they ran was me in the hotel lobby nowhere near my art, and the pull quote used was “video artist from the US strongly favors Obama”, which also had nothing to do with my artwork.

Shortly thereafter, I was contacted by a curator organizing a large traveling exhibition to celebrate Dr. King’s 80th birthday. When I asked why she wanted me in this exhibition, she mentioned the article. Somehow, because I was painted as an Obama-supporting artist, she felt I should be included in the show. I thought about it for some time and looked for inspiration in MLK speeches and events wondering how I could make my work at the time appropriate for such an exhibition when I came across this quote from a 2008 speech by then-senator Barack Obama on the 40th anniversary of the assassination of MLK:

“Dr. King once said that the arc of the moral universe is long, but that it bends toward justice. But what he also knew was it doesn’t bend on its own. It bends because each of us puts our hands on that arc and bends it in the direction of justice.”

I adapted an installation I previously had installed as a grid to form an arc and called it Arcing. The installation used lollipops drilled directly into the wall. Over time they slowly melt and change. Sometimes slow and just a little, sometimes rapidly and intensely. It was all left to the chance of the weather and humidity.

I flew to New York in January 2009 to install the work. Serendipitously, I watched Barack Obama be sworn into office from a giant jumbotron in Times Square blocks from the gallery where the exhibition was. Later that month I’d start a full-time job as a professor in academia and make the San Francisco Bay Area my permanent home. As I reflected on my time abroad, my entire practice in teaching, making, and researching shifted to environmental sustainability and regenerative design as a result of my time abroad which ended with this exhibition. Living in all of those places, being a part of, and witnessing the global voyage of our resources-to-goods-to-trash inspired me to pivot my work. The literal sight of our goods being mass produced in Asia, sent to the US, sent back as trash, empty shipping containers becoming makeshift homes in remote parts of Africa, the systematic rejection of mass transportation in the US compared to the complexity and ease of the trains in the UK, traveling from port to port to return to the port of Oakland where these same shipping containers come in and out. I needed to put my hands firmly on the arc and bend it toward environmental justice using my voice as a designer to do so.

I got asked to make work about MLK for an exhibition in New York because a newspaper in Madrid said I supported Obama. I was invited to Madrid because a curator had seen me give a talk at a museum in London. I was in London because I took a year off to travel, make work, and new connections. The video the Madrid curator asked me to show was a simple video projection filmed on the iconic Santa Monica pier ferris wheel in Los Angeles. Traveling up and down, in a continuous loop the viewer is always in relation to the flashing lights, the mechanical and repetitive sounds, and the metal bars connecting the cars to a larger wheel as it flows. In describing my work, the reporter from El País accurately said my other works at the time were far more “radical.” But the simplicity for many is mesmerizing, the analogy of life moving up and down, small parts connected to a larger whole. Last week I was asked to introduce myself in 3 emojis. I scrolled my phone looking for something I thought symbolized systems thinker and I used 🎡 (the ferris wheel). Everything is connected. Every time the wheel spins it bends an arc.

The question before us today

Designers, scientists, activists, mothers, fathers, students, teachers, engineers, poets - each of us must put our hands on that arc and bend it towards justice with dangerous unselfishness. While property lines, city, and national borders can be drawn; status symbols, degrees, and economics measured, we are all here together on the same planet, using the same resources. Our stories are all connected. We are all connected.

Trying to grab the arc to bend it towards yourself, living in excess, carelessly consuming, and wasting, might give you more at the moment, but will only work against the greater good. All of us are connected to that arc, we all have the power to bend it. It’s up to us to decide which way to bend it.

Today, on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Day, the United States celebrates a federal holiday. Despite it being a day off of work and school for many, it’s also been designated by Congress as a national day of service - not a day off, but a day on. It’s fitting to honor the legacy of Dr. King unselfishly serving others. Something to remember not only today, but everyday.